The Couriers of Herodotus grew from my interest in aviation history. I have always been interested in history, but with aviation serving in my life as both vocation and avocation, it seemed my primary source of reading material fell in the area of aviation history.

After at least a decade in the profession, I discovered material regarding the early days of air mail service and had the epiphany that the airline industry that we know today is the direct descendant of the first official air mail flights of 1918.

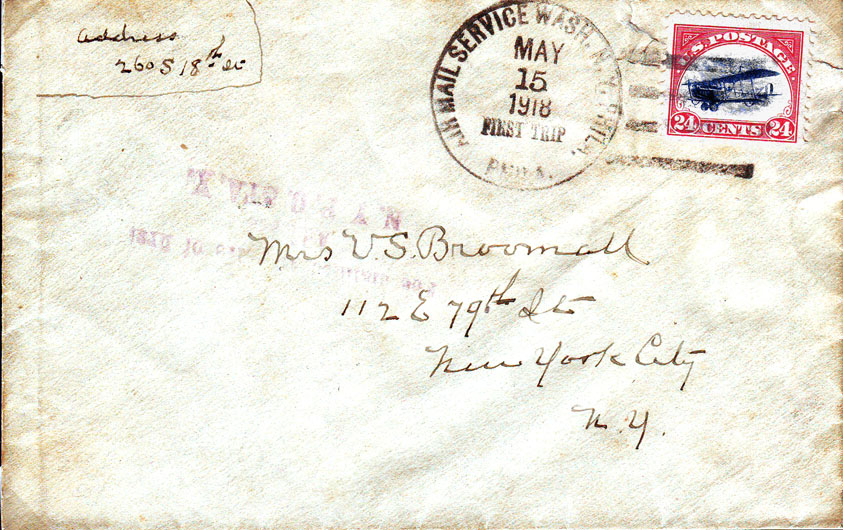

If the airline industry had a birth certificate, it would be dated May 15, 1918.

On that day, the first scheduled service began between Washington, D.C. and New York with a stop and transfer in Philadelphia. The day’s operation was a success… mostly. The initial leg from D.C. was assigned to Lt. Boyle, whose primary qualification, beyond his recent graduation from the Army’s flight school, was his engagement to the daughter of the Interstate Commerce Commission. What story of airline industry history would be complete without some measure of political influence?

(The circumstances of the industry’s birth and the inauspicious contribution made by Lt. Boyle, might be a story for another day. Back to The Couriers…)

It became apparent that the air mail flights were a turning point in aviation. Aviation has always been heavily influenced by weather conditions, even during combat operations in World War One, but air mail service could only be a success if flights were reliable and dependable. The air mail service was the first application of aviation that made a commitment to operating every day (and later, night) in whatever weather conditions existed. These brave aviators pushed the existing boundaries of both the flight conditions and the equipment to new levels.

But why would men risk their lives so that young Timmy in Boston could thank Aunt Edna in Chicago for the new scarf she knitted for his birthday? Or, so that a few dollars could be saved by transacting a business deal a day or two earlier? Each of these early brave pioneers had unique motivations perhaps but the one thing they had in common was a desire to prove that aviation could be a reliable, commercial entity and not just a novelty for county fairs, or a weapon of war.

As I learned more, I viewed things from the perspective of my growing experience in modern airline operations.

I was impressed to find that even with what seems now like primitive equipment and operations support, the air mail service quickly established completion statistics more than 90%!

I wanted to learn more about the experiences of the pilots and the challenges they faced every day. In current airline operations, anything unusual or noteworthy is documented, typically by the captain, in a brief report. I figured that no self-respecting government operation would miss an opportunity to generate paperwork and more importantly the infrastructure to process said paperwork. After reading Aerial Pioneers by William Leary (University of Georgia), a work I consider to be the best overall account of this time period in aviation, I learned that the National Archives had flight reports from the Army pilots who operated the initial three months of service as a means to gain flight experience. There were also reports and personnel files the pilots who worked for the United States Post Office from August of 1918, when the USPS took over operations, until the mail contracts were let to private contractors several years later.

I was pleased to find that any person who invests a little bit of effort to obtain credentials could go to the Archives and access the actual records. Touching and reading this material first-hand gave me insight of the personalities. In addition to the flight reports, I saw memos written by supervisors, admonishing pilots for failing to turn in expense reports on time or in sufficient detail.

These pilots were suddenly real individuals, not unlike my co-workers at the airline.

As I became more impressed by their accomplishments, and amazed that so few of my fellow pilots knew about their story, I wanted to find some way to honor their efforts.

I tried to find lasting legacies that these pilots brought to the industry and one thing that stuck out was that these aviators were driven to help each other to advance the field of aviation. Just as mariners always provided aid to fellow mariners, so went the early aviators.

I learned, by writing operations bulletins and memos at the airline, that the best research or the most efficient new technique is lost if the attention of the reader isn’t held to the end of the document. As anyone who has been around a coffee pot at a local airport on a rainy Saturday knows, even aviators who no longer actively fly, can, and do, communicate their experiences to others. Does death mark the end of this desire? I thought back to all the timely advice I received and wondered if there was something else going on?

I searched reports of accidents and incidents that related to challenges that we face in contemporary flight operations and found that I could develop these actual events into what I feel is an interesting journey by one young person who understands the passion of aviation and the foundation laid by those who came before.

The Couriers of Herodotus was born. I hope you will enjoy the story.